Cantos Cautivos

Cantos Cautivos

Cantata Santa María de Iquique

- Music piece by:Luis Advis

- Testimony by:Alfonso Padilla

- Experience in:

Between March 1974 and July 1975, I had the opportunity to arrange about 200 songs and direct the production of the Cantata de Santa María de IquiqueWork about the 1907 massacre of miners in the city of Iquique (Northern Chile). Composed by Luis Advis in 1969 and recorded by Quilapayún in 1970.. In truth, the prison was my conservatoire. That’s where I learnt the basics of the profession of musician.

How did we get the lyrics and tunes for the music? In my case, during the whole period I spent in jail, I collected about 700 songs in ten notebooks.

The first two were written from what numerous political prisoners remembered. The lyrics of the remaining ones were taken from popular music magazines that our relatives would send us, and also from vinyl LPs.

We took in records that were, in fact, forbidden, or their possession would seriously endanger our safety. They were hidden in sleeves of records by singers that were inoffensive to the dictatorship. Sometimes, we would also ‘pay’ a guard with a liquor bottle.

That’s how we took records into the prison by Atahualpa Yupanqui, Mercedes Sosa, Chico Buarque, Carlos Puebla, Joan Manuel Serrat, Mikis Theodorakis, Joan Báez, Violeta Parra, Daniel Viglietti and the main figures of the

Two comrades would spend a day taking down the lyrics of the songs, and I would spend two days listening attentively to transcribe the harmonic and rhythmic accompaniment, which I would write down in the usual manner that popular music operates. On the fourth day, the record would leave the prison.

In each of the collective cells – one for forty prisoners and two for sixty prisoners – we had three record players belonging to the political prisoners. We would listen to music on this basic equipment as we liked, but not loudly, to avoid surprise raids by guards.

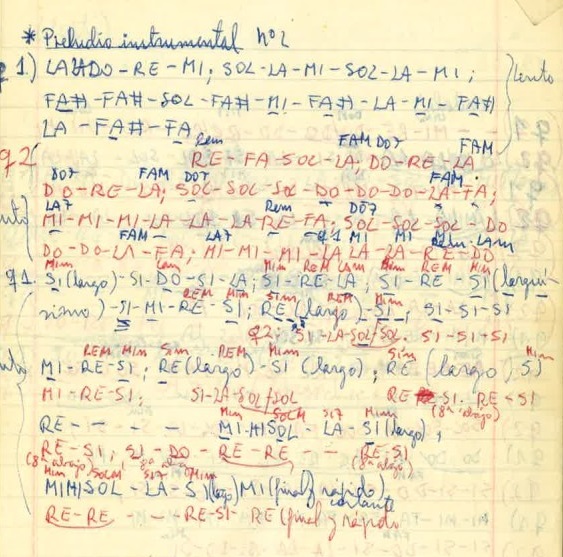

The process of producing the Cantata Santa María de Iquique lasted little over two months, between the beginning of March and the second fortnight of May 1975. After writing down the lyrics from the record in a couple of days, I listened to the music for a month very carefully. Since I didn’t know how to read or write music, I annotated it with the note and chord names that accompanied the melody.

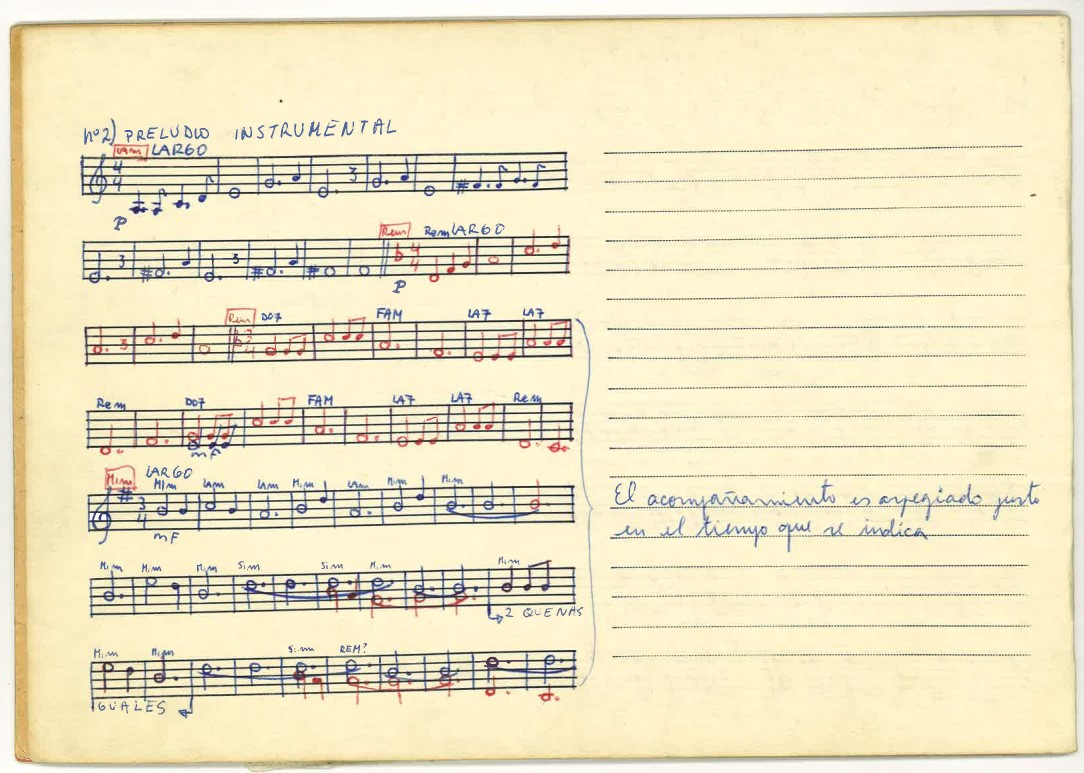

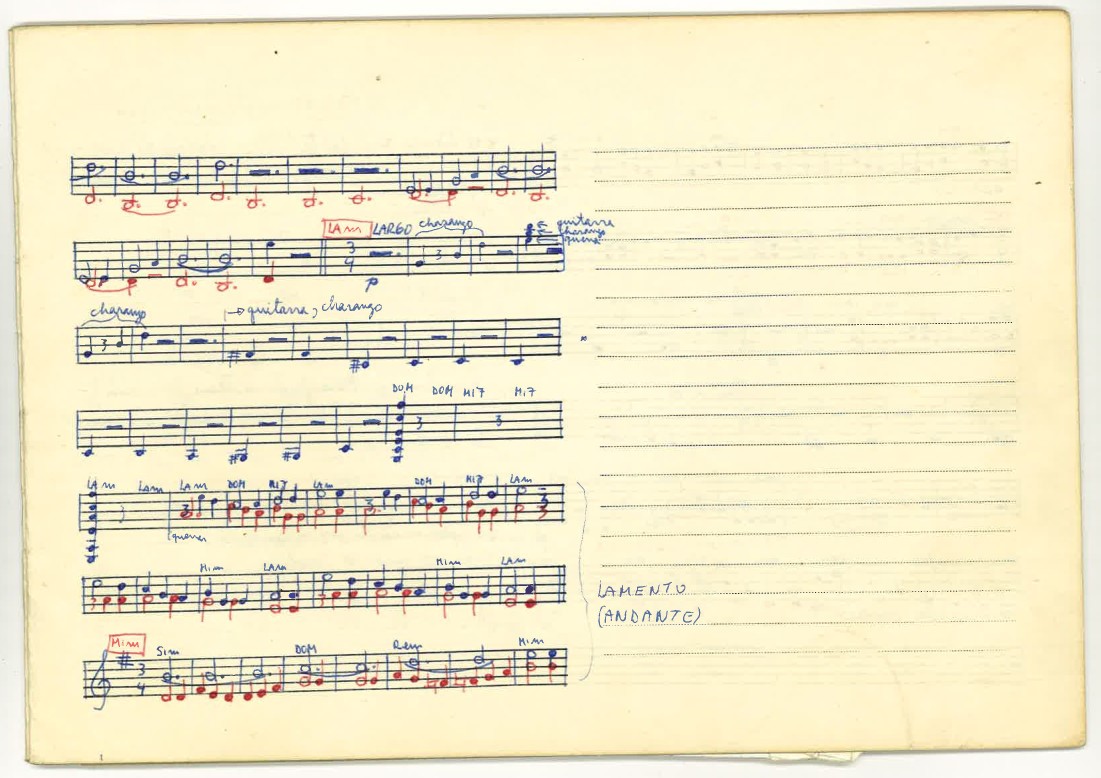

During that time, an economics professor from the University of Concepción arrived and brought a keyboard accordion and a book with scores with him. There was an introduction to music theory in this book and I devoured it straight away. That’s how I learnt to write music between June and July 1975 and transcribed the Cantata Santa María on a score with the melodies and the accompanying chords.

Nevertheless, my knowledge was rudimentary so the notation was imprecise; the worst example is the prelude, which is in 3/4 and I wrote in 4/4. (On the Quilapayún recording there are rhythmic parts that are not 100% fixed, there is some improvisation, or rather, they used a freer agogic for brief periods. All this is normal in traditional and popular music.)

I learnt the work by heart and we rehearsed as it is customary for popular musicians: I taught every part, every melodic line of the quenasAndean traditional flute, made of reed or wood., every harmonic accompaniment, strumming and bomboLarge bass drums used in various regions in Latin America. rhythms, through repetition. Everyone learnt their part by heart, by the way.

The rehearsals lasted a month and we held them in a tiny punishment cell with walls and a door so thick, that outside of it nothing could be heard. That’s why the performance of the piece was a complete surprise for the political prisoners. During the ‘concert’ dozens of common prisoners and guards came to listen.

This experience showed us the undoubted force that art has, mostly – in the case of music – those pieces, works or songs of popular, traditional or classical music that, bring masterly together a profound text, with appropriate music and an enormous dose of humanism.

Tags:

Published on: 04 December 2019

Related testimonies:

- How We Resemble Each Other (En qué nos parecemos) Luis Cifuentes Seves, Campamento de Prisioneros, Estadio Nacional, September - November 1973

During the 1960s, the group Quilapayún popularised this old Spanish song in Chile. Víctor Canto and I performed it as a duet in Santiago’s National Stadium, which had been converted into a concentration, torture and extermination camp.

- How We Resemble Each Other (En qué nos parecemos) Scarlett Mathieu, Campamento de Prisioneros Cuatro Álamos, 1974

In Cuatro Álamos, I was profoundly marked by the singing of a current detained-disappeared named Juan Chacón. He sang ‘En qué nos parecemos’, a love song from the Spanish Civil War. It remained engraved in me because that comrade disappeared from Cuatro Álamos.

- May the Omelette Flip Over (Que la tortilla se vuelva) Claudio Melgarejo, Comisaría de Concepción, November 1973

I spent a week in captivity, in November 1973. I didn’t hear many songs, but the most popular ones sung by my comrades were 'Venceremos' (We Shall be Victorious) and 'Que la tortilla se vuelva' (May the Omelette Flip Over), also known as 'The Tomato Song', which portrays the bosses' exploitation of the workers.

- Free (Libre) Marianella Ubilla, Campamento Prisioneros Estadio Regional, Christmas 1973

I was taken prisoner on 23 November 1973, at the University of Concepción. In the Regional Stadium of Concepción, we had to sing the National Anthem every day.

- I’m Not from Here - To my Comrade, my Love (No soy de aquí - A mi compañera) Alfonso Padilla Silva, Campamento Prisioneros Estadio Regional, 25 December 1973

The choir of male prisoners sang a piece called 'A mi compañera' (To my comrade, my love) to the music of 'No soy de aquí, ni soy de allá' (I'm not from here, nor from there) by Facundo Cabral.

Testimonies from the Cantos Cautivos platform can be cited and shared as long as they are attributed (including the author, our project’s name and URL), for non-commercial purposes and without modifications, as per the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives Creative Commons licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Authorisation is required for 1) any reuse different from citations and sharing via the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license of the platform data and its associated metadata, and 2) any use in events, concerts, plays, films, etc., of musical works written or recorded by project participants. To that end, we request that you send a proposal at least one month in advance to contact@cantoscautivos.org. For uses of musical works written or recorded by people outside the project, please contact copyright holders.